AI Transcription at the Frontline: Phenomenological and Ethical Challenges in Probation Settings Through Lisbeth Lipari’s Listening Being Framework

The UK Ministry of Justice is exploring artificial intelligence for automatic transcription of probation supervision conversations. If proof of concept is proven and a decision is made to deploy this technology more widely, then some might say that this represents more than a technological upgrade. They might even suggest, with some conviction, that this development might constitute a fundamental disruption of the ethical and phenomenological foundations that make effective probation work possible [1]. While policy makers frame AI transcription as a potential solution to administrative burdens, communication scholar Lisbeth Lipari’s groundbreaking work on “listening being” reveals deeper challenges to the very essence of what might be described as the rehabilitative encounter [2][3][4].

Lipari’s phenomenological approach to listening offers an interesting critical lens for understanding why AI transcription poses risks that extend far beyond technical accuracy or privacy concerns [3]. Her framework reveals that authentic listening is not merely a skill or tool but an ontological experience—a way of being that creates the conditions for ethical encounter and meaningful human transformation [3]. When AI systems mediate these encounters, they risk fragmenting what Lipari identifies as the fundamental intersubjective space where healing and change become possible [4][5].

Lisbeth Lipari’s Phenomenological Framework: Beyond Information Processing

Listening Being as Ontological Experience

Lipari’s most radical insight challenges conventional understanding of listening as merely information processing or communication skill [3]. In her seminal work “Listening, Thinking, Being,” she argues that authentic listening constitutes our very being: “when I’m listening, really listening as opposed to hearing or interpreting, I AM listening” [3]. This ontological understanding positions listening not as something we do, but as something we are—a fundamental mode of human existence that creates space for ethical encounter with radical alterity [3][4].

This perspective draws on phenomenological traditions from Heidegger and Levinas, combined with Eastern philosophical insights about emptiness and non-attachment [3]. For Lipari, genuine listening requires what she terms “inner emptiness”—making “a space where I am not” to genuinely encounter the other without imposing predetermined categories or expectations [3]. This challenges the very premise of AI transcription systems, which necessarily operate through categorical frameworks and algorithmic processing that transform open encounter into data capture [6][7].

The Ethics of Attunement

Central to Lipari’s framework is the concept of “ethics of attunement”—an approach to ethics grounded not in rules or outcomes but in “awareness of and attention to the harmonic interconnectivity of all beings and objects” [8][9]. This attunement requires what she describes as phenomenological presence: “standing in proximity to your pain… fully present to the ongoing expression of you” without needing to understand, categorise, or control the encounter [3].

This ethics of attunement directly conflicts with the instrumental logic driving AI transcription implementation in probation services [1]. Where Lipari emphasizes “no grasping, no holding,” AI systems are fundamentally designed to grasp, capture, and systematically process human expression [3]. The technological imperative to document and quantify transforms what should be an open ethical encounter into an administrative data collection exercise [7][10].

Radical Alterity and Intersubjective Space

Perhaps most critically for probation practice, Lipari’s work highlights how authentic communication occurs in the “between”—the intersubjective space where meaning emerges through mutual presence rather than through information transmission [3][4]. This intersubjective space requires what she calls encounter with “radical alterity”—recognition that the other remains fundamentally unknowable and irreducible to our conceptual frameworks [3][4].

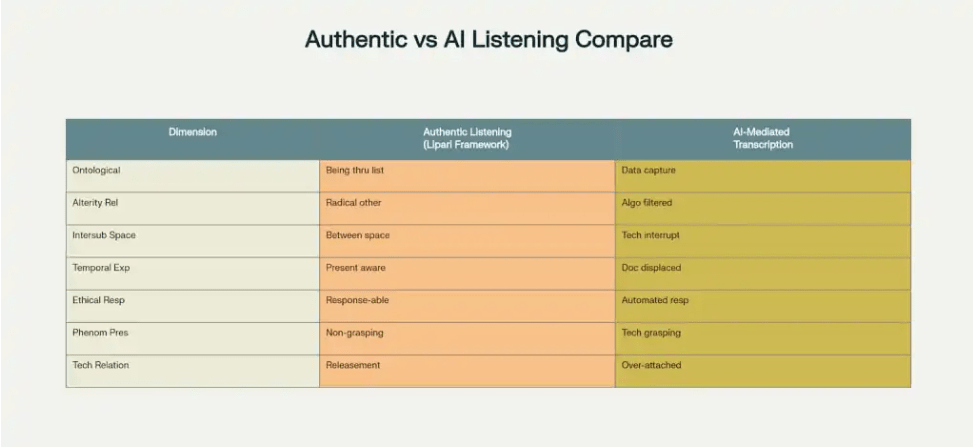

Authentic Listening vs AI-Mediated Transcription: A Phenomenological Comparison

AI transcription systems fundamentally disrupt this intersubjective space by introducing a third party—the algorithmic system—into what should be a dyadic encounter [6]. The technological mediation shifts attention from present-moment engagement to future documentation, compromising the phenomenological presence that Lipari identifies as essential for ethical responsiveness [3]. When probation officers must attend to AI recording systems, they lose capacity for the “gathered hearkening” that enables authentic listening being [3].

Phenomenological Disruption in Probation Practice

The Commodification of Listening

Lipari’s framework reveals how AI transcription transforms listening from an ontological experience into what can be termed “commodified documentation” [3]. Where authentic listening being creates space for transformation and healing, AI-mediated recording reduces complex human expression to textual data that can be processed, analysed, and archived [7][10]. This commodification represents what Lipari warns against: treating listening as mere information processing rather than ethical encounter [3].

The implications for probation practice are profound [1]. Effective supervision depends on officers’ capacity to create conditions where service users feel heard, understood, and met in their full humanity [11]. When AI systems mediate these encounters, they risk transforming probation work from a relational practice focused on human transformation into a data collection exercise prioritising administrative efficiency over ethical encounter [1][10].

Disrupted Present-Moment Awareness

Lipari emphasises that listening being occurs in what she calls the “nowhere of the here and now”—a state of present-moment awareness that transcends past categorisations and future projections [3]. This temporal dimension proves crucial for probation work, where transformation often occurs through encounters that disrupt service users’ established narratives and create new possibilities for self-understanding [11].

AI transcription systems fundamentally compromise this present-moment awareness by shifting focus from immediate encounter to future documentation [1]. When officers must ensure AI systems capture conversation content, their attention becomes divided between being present with the service user and managing technological requirements [12][13]. This temporal displacement undermines what Lipari identifies as the essential “emptiness” required for authentic listening—the capacity to encounter each moment without predetermined agendas or outcomes [3].

Phenomenological Disruption: How AI Transcription Fragments Lipari’s Listening Being Framework

Loss of Embodied Communication

Lipari’s phenomenological approach emphasises that authentic listening encompasses far more than auditory processing [9][14]. Her concept of “polymodality” includes “gesture, posture, facial expression, and eye gaze; sound features such as prosody, pitch, rhythm, and inflections; relational features such as proximity, touch, eye contact” [14]. This embodied dimension of communication proves essential for probation practice, where much therapeutic work occurs through non-verbal attunement and somatic presence [15].

AI transcription systems, however, reduce this rich multimodal communication to linguistic text, losing crucial emotional and relational information [7]. The technological focus on speech-to-text conversion overlooks what Lipari identifies as the “emptiness of awareness itself”—the space of non-conceptual presence that enables deep listening [3]. When probation officers become oriented toward ensuring AI systems capture verbal content, they may lose attunement to the embodied dimensions of communication that often convey the most therapeutically relevant information [13][16].

Critical Realist Analysis: Structural Mechanisms and Power Dynamics

Technology as Structural Mechanism

From Lipari’s phenomenological perspective, combined with critical realist analysis, AI transcription systems operate as structural mechanisms that generate specific forms of alienation and disconnection [3]. The technological imperative to capture and process human expression reflects what Heidegger (referenced extensively by Lipari) identifies as the danger of “calculative thinking” overwhelming “meditative thinking” [3].

This calculative orientation transforms probation encounters from spaces of ethical responsiveness into data production sites [7][10]. The structural mechanism operates independently of individual intentions—even well-meaning officers using AI transcription systems become embedded within technological logics that prioritise documentation efficiency over phenomenological presence [3]. This represents what Lipari, following Heidegger, warns against: technology that “captivates, bewilders, dazzles, and beguiles” human beings into accepting instrumental rationality as the only valid approach to human encounter [3].

Algorithmic Mediation of Ethical Responsiveness

Lipari’s concept of ethical responsiveness—the capacity to respond to the “call of the other” without seeking to control or master—becomes compromised when AI systems mediate human encounter [3][4]. Algorithmic processing necessarily operates through categorical frameworks that reduce the radical alterity of the other to manageable data points [6][7]. This transformation undermines what Lipari identifies as fundamental to ethical encounter: the willingness to be disrupted by otherness that exceeds our conceptual frameworks [3][4].

In probation contexts, this algorithmic mediation of ethical responsiveness manifests as systems that claim to enhance officer decision-making through “objective” data analysis [1]. However, Lipari’s framework reveals how such claims mask the violence of reducing human complexity to algorithmic categories [3]. When service users’ expressions are filtered through AI transcription systems, their radical alterity becomes domesticated within technological frameworks that prevent the kind of disruptive encounter essential for transformation [4][17].

Implications for Probation Practice and Policy

Preserving Spaces of Unmediated Encounter

Lipari’s framework suggests that effective probation practice requires what she terms “releasement”—the capacity to remain engaged with technology while maintaining the ability to “let go at any time” [3]. This points toward implementation strategies that preserve spaces of unmediated encounter within AI-augmented supervision [1]. Rather than recording entire supervision sessions, services might use AI transcription selectively, maintaining periods of pure presence where officers can practice listening being without technological mediation [3].

Such an approach would recognise what Lipari identifies as essential: that some aspects of human encounter cannot and should not be technologically mediated [3]. The phenomenological depth required for therapeutic transformation often emerges in moments of silence, non-verbal attunement, and embodied presence that AI systems cannot capture or replicate [14][13].

Training in Phenomenological Awareness

Lipari’s work suggests that effective integration of AI transcription requires training that goes far beyond technical competency [3]. Officers need development in what she calls “listening being”—the capacity to create intersubjective space where authentic encounter becomes possible [3][4]. This would include cultivating awareness of when technological mediation enhances versus disrupts ethical responsiveness, and developing skills for shifting between mediated and unmediated modes of engagement [3].

Such training would draw on Lipari’s insights about the relationship between listening and thinking, helping officers develop what she terms “meditative” rather than merely “calculative” approaches to their work [3]. This phenomenological awareness could enable more skillful use of AI transcription—employing it as a tool while preserving the deeper capacities for listening being that make effective supervision possible [3].

Designing Ethically-Informed AI Systems

Lipari’s framework suggests directions for AI system design that could minimise phenomenological disruption while preserving administrative benefits [3]. Rather than continuous recording, systems might capture key decision points or factual information while leaving space for unmediated relational work [1]. Interface design could prioritise officer attention on the service user rather than technological management, perhaps through voice-activated systems that respond to natural speech patterns rather than requiring conscious interaction [6].

Most importantly, system design should acknowledge what Lipari identifies as the irreducible mystery of human encounter [3]. Rather than claiming to comprehensively capture supervision conversations, AI transcription could be framed as partial documentation that supplements rather than replaces human judgment and relational awareness [3][7].

Toward a Phenomenologically-Informed Practice

Integrating Technological Efficiency with Ethical Encounter

Lipari’s phenomenological framework does not require rejecting AI transcription entirely, but rather developing what might be termed “technologically-mediated ethics of attunement” [3]. This would involve using AI systems in ways that preserve rather than compromise the fundamental capacities for listening being that effective probation work requires [3].

Such integration would recognise the legitimate administrative benefits of AI transcription while maintaining what Lipari identifies as essential: the capacity for “inner emptiness” and openness to radical alterity that creates conditions for human transformation [3]. Officers could use AI-generated transcripts for case planning and documentation while ensuring that supervision encounters themselves preserve spaces for the kind of present-moment awareness and phenomenological presence that Lipari identifies as fundamental to ethical encounter [3].

Building Resilience Against Technological Colonisation

Perhaps most importantly, Lipari’s work provides conceptual resources for resisting what might be termed the “technological colonization” of probation practice [3]. Her emphasis on releasement and non-attachment offers guidance for maintaining human agency within increasingly AI-mediated work environments [3]. Officers trained in listening being would be better equipped to use AI transcription skilfully while preserving the deeper capacities for ethical responsiveness that technology cannot replicate [3][4].

This resilience becomes crucial as AI systems become more sophisticated and potentially more seductive in their claims to enhance human judgment [6][7]. Lipari’s phenomenological framework provides grounding for recognising what remains irreducibly human in therapeutic encounter—the capacity for mutual presence, ethical attunement, and transformative encounter with radical alterity [3][4].

Conclusion: Listening Being in an Age of Algorithmic Mediation

Lisbeth Lipari’s phenomenological framework reveals dimensions of the AI transcription challenge that remain invisible to purely technical or legal analyses [3]. Her insights demonstrate that the stakes extend far beyond issues of accuracy, privacy, or administrative efficiency to fundamental questions about the nature of human encounter and ethical responsiveness [3][4].

The integration of AI transcription into probation practice represents a critical moment for determining whether technological advancement serves or undermines the deeper purposes of criminal justice work [1]. Lipari’s work suggests that effective integration requires more than technical training or legal compliance—it demands cultivating the phenomenological awareness necessary to preserve authentic human encounter within increasingly mediated environments [3].

Ultimately, the challenge is not choosing between efficiency and ethics but developing approaches that honour both administrative needs and the irreducible mystery of human transformation [3]. Lipari’s concept of listening being provides a foundation for such integration, offering guidance for maintaining ethical responsiveness while navigating the complex realities of contemporary probation practice [3][4]. The future of effective supervision may depend on practitioners’ capacity to embody this integration—remaining technologically competent while preserving the deeper capacities for listening being that make genuine transformation possible [3].

- https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-020-05323-1

- https://denison.edu/people/lisbeth-lipari

- https://lisbethlipari.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/listeningthinkingbeing.pdf

- https://academic.oup.com/ct/article/14/2/122-141/4110461

- https://oxfordre.com/communication/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228613-e-58?d=%2F10.1093%2Facrefore%2F9780190228613.001.0001%2Facrefore-9780190228613-e-58&p=emailAcKLHKTA7CU1I

- https://www.raco.cat/index.php/Artnodes/article/view/374038

- https://waywithwords.net/resource/privacy-in-transcription-transcribes/

- https://www.psupress.org/books/titles/978-0-271-06332-4.html

- https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/20839473-listening-thinking-being

- https://globibo.blog/ethical-considerations-in-automated-transcription-services/

- https://revistaprospectiva.univalle.edu.co/index.php/prospectiva/article/view/1126

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0048721X.2022.2053037

- https://journals.library.ualberta.ca/pandpr/index.php/pandpr/article/view/29464

- https://francovich.wordpress.com/2018/12/05/listening-thinking-being/

- https://ojs.lib.uwo.ca/index.php/fpq/article/view/10846

- https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/10.3397/IN_2024_3536

- https://doubledialogues.com/article/alterity-and-antipathy-the-plight-of-anti-levinasian-man-in-becketts-the-expelled-and-other-novellas/

Leave a comment